IFV challenges compared to APCs

The IFV’s benefits are offset by several features that have ramifications for the utility of the vehicles.

Comparative weight of IFV and APC

Both the Lynx and the Redback are heavy and large. The Lynx weighs 45 tonnes while the Redback weighs 42 tonnes, and both are approximately 3.6 metres high. The weight is a function of the protection level that the Army has sought, as well as the powerful armaments they carry. Contemporary APCs such as the Piranha and Eitan are lighter than the Lynx and Redback, but that’s mainly due to their lighter armour and being wheeled. As is discussed below, the weight of the Phase 3 vehicles has implications for the ADF’s ability to deploy them on operations.

Number of soldiers carried

The Lynx and Redback are designed to carry six dismounts in their passenger compartments. Both IFVs have a crew of three. This means that the maximum number of soldiers that the IFV carries is less than for the vehicle it’s replacing, as well as for contemporary APCs such as the Piranha and Eitan, which can carry between five and 12 dismounts. While the Army will be able to transport fewer soldiers per vehicle, this continues a longstanding trend in warfare: as weapons become more lethal, fewer soldiers are visible on the battlefield. Additionally, the IFV has the ability to carry soldiers—depending on tactical circumstances—directly to the objective, whereas with an APC they must dismount at some distance and are likely to incur casualties as they fight to the objective.

Cost, including that of losing an IFV

The IFVs’ estimated cost of up to $27 billion includes considerable FIC expenses as well as the cost of five years of sustainment.

The vehicle itself, however, is only part of what constitutes a capability. An IFV requires a crew and passengers, who also come with a cost. The three crew and six dismounts, including their training and education in addition to wages and other expenditures, represent an investment on the part of the government. While some may find it disquieting to assign soldiers a monetary value, it’s the reality. The death of a soldier involves both the loss of the expenditure consumed to achieve the soldier’s proficiency and the cost of producing a replacement. We can cut corners on training to save money, but the result is low-quality soldiers who die quickly in combat, as the war in Ukraine demonstrates. The same can be said of the difference in cost between a vehicle with a high-protective value and a vehicle with a lesser one. When the government considers the IFV acquisition it might also include in its deliberations the cost of replacing the soldiers who might have been lost in a vehicle with a lower level of protection.

In addition to financial costs, the loss of a vehicle or vehicles potentially comes with a tactical cost, including the possibility of operational failure. If too many vehicles are damaged or destroyed, the result may be a loss of tactical momentum to the point that an attack comes to a halt with the objective unmet. In addition, casualty evacuations may hamper manoeuvre or distract a commander, again possibly leading to mission failure. Thus, less robust vehicles, which have lower battlefield survival prospects, come with greater tactical risk that includes not just the potential for more casualties but also momentum loss leading to mission failure.

Figure 4: A Lynx KF41 IFV firing a 30-mm tracer round on a test range in Germany

Source: Rheinmetall Defence Australia, online.

The strategic environment

It’s widely understood by the government, Defence and the national security community that Australia is facing a more challenging and dangerous future. The potential threats Australia will need to deal with—notably the multiplying effects of a changing climate and a more direct Chinese military presence in Australia’s near region—are becoming more evident as well as increasing in intensity. As the Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence, Richard Marles, has observed, this is the most strategically complex period since the end of World War II.3 China is challenging the rules-based order, while climate change represents another possible threat to the security of Australia and the region. Additionally, weapons proliferation is taking place, and non-state groups now routinely gain access to powerful and lethal combat systems that were formally the remit of only well-organised state-based militaries. Consequently, operations against such well-armed groups now require levels of force protection that were previously considered unnecessary.

The previous Australian Government, in its 2020 DSU accepted that a greater investment in the nation’s security architecture was needed if the country were to remain safe and its interests assured. The September 2021 announcement of the security agreement between the US, the UK and Australia further underscored the government’s concerns. In response to a security environment in which some countries have become more assertive and coercive, the Australian Government has announced its intention to acquire a range of new platforms. How it will fund those acquisitions is not clear; for example, the nuclear-powered submarine program will require well above $100 billion. As noted by writers in

The Strategist, the government will need to allocate additional monies if the ADF is to achieve those procurements.4

The 2020 DSU’s guidance instructs the ADF ‘to

shape Australia’s strategic environment,

deter actions against our interests and, when required,

respond with credible military force’.5 The report also admits that, while high-intensity conflict in the Indo-Pacific remains unlikely, the possibility of its occurrence is less remote than previously believed. Other commentators haven’t limited themselves to such diplomatic language: one senior bureaucrat stated that we ‘again hear the beating drums of war’.6 Across much of the national security community, the forecast for conflict is expressed in alarming terms. For example, ASPI’s Malcolm Davis put the odds of war with China over Taiwan at 70% to 80%.7 Another analysis put the estimate at 45%.8 Similar language is heard in the US where government officials increasingly anticipate a move by China against Taiwan.9

Unfortunately, the 2020 DSU, other than requiring the ADF to respond with a credible force, lacks specificity both on the nature of the war the ADF is to prepare for and its intensity. Perhaps such detail is in non-public documents. What can be said about the future security environment is that, even if Australia has no interest in war, war may have an interest in Australia.

Waging modern war

For most of humanity’s war-fighting history, the waging of war could be conveniently divided into war on the land, on the sea, and later in the air. In turn, the land, sea and air have each been the domain of a particular service (an army, a navy or an air force) that ‘owned’ the preparation for and waging of war in its particular domain. In friction with this idea of domain ownership is the reality that there’s always been a degree of overlap between the three domains. In recent decades, however, technological advances have meant that the overlap between the domains is large and growing. As a result, each domain can affect actions in another without the impediment of distance far more than in the past. Moreover, due to improvements in sensor technology, the time is fast approaching in which, when a target is found, a commander can assign to it the best available shooter, no matter which service it belongs to. With the addition of the space and cyber domains, warfare now exists in, through and across five domains.

In contemporary war, a commander coordinates the effects of land, sea, air, space and cyber assets across a joint battlespace to meet a common plan and objective. Today, the overlap among the domains is ever widening and, consequently, the Australian Army will be able to influence the other domains to a much greater extent than formerly possible. Within a theatre-wide space, depending on the circumstances, warfare could range from a close contact in which adversaries can see each other to a battle in which a commander allocates the fires of numerous shooters, in different domains, upon a distant target. What this means is that all ADF platforms, ranging from a future IFV to a future frigate, must be able to coordinate and share information with other systems in order to achieve desired outcomes. They must all be able to wage war not as individual parts but as components of a larger system.

The specifications for the IFV required tenderers to provide a vehicle that would be capable of operating in this system-dominated way of war as future defence investment and development bring more of this aspiration into being. The Lynx and Redback are expected to contribute to the fight beyond the range of their guns or the dismounts they carry. The sensors and communication technologies they possess could, with the assistance of the other services, allow them to serve as nodes in a theatre-sized contest, in a connected way, supporting all domains. Of course, other technologies, such as a low-orbit satellite system, could also fulfil or supplement that function, if the government prefers.

The Russian–Ukrainian war and the future of armour

The most recent conflict that can help inform the government’s decision on LAND 400 Phase 3 is the current war in Ukraine. It’s far too early to discern its enduring lessons, but some observations are possible.

The toll of war in Ukraine

To even the unobservant, it’s clear that the Ukrainians have destroyed a large number of Russian tanks and other armoured vehicles. Reliable and precise figures of Russian losses aren’t available, but one estimate suggests that as of late May the Ukrainians had destroyed about 1,000 of the invader’s tanks.10 As of mid-June, Ukraine claims to have destroyed:

- 1,440 tanks

- 3,528 armoured combat vehicles

- 772 artillery systems

- 179 helicopters.

Ukrainian sources also say that the Russians have suffered more than 32,000 casualties.11

The images of destroyed Russian vehicles that litter the battlefields of eastern Ukraine (Figure 5) have led some to conclude that the tank, and other armoured vehicles more generally, have had their day.12 An article in The Atlantic concludes that Russian losses illustrate the diminishing value of large and heavy military platforms. The sinking of the Russian cruiser Moskva illustrates the risks large ships also face.13

Figure 5: A destroyed Russian main battle tank, July 2022

Source: Ukrainian Defence Ministry, online.

Why Russian armour has proven vulnerable

Russian armour has proven vulnerable to a single soldier armed with an anti-tank weapon, such as the US Javelin or the UK Next Generation Light Anti-Tank Weapon, as well as to armed drones including the US Switchblade and other weapon systems such as traditional artillery strikes. Some opinion makers believe that such weapons call into question the survivability of armoured vehicles. Clearly, a contributing factor to losses in Ukraine has been the systemic failings of the Russian Army in its conduct of Putin’s war.

Although it initiated the war, Russia has proven incapable of waging a joint war of manoeuvre, leading one commentator to highlight Russian military incompetence in the destruction of its armoured fighting vehicles and went on to describe its performance as ‘spectacularly poor’.14 Compounding Russia’s losses is its use of platforms that lack modern levels of protection, including active protection systems. Russia’s performance can be summarised as follows:

- The Russian force that invaded Ukraine contains a large number of poorly trained conscripts. Green troops never fare well against troops with good training.

- The Russian Army seems to have forgotten the practice of combined arms and joint warfare. All too often, tanks and other armoured vehicles have advanced without support. Since World War II, it has been known that unsupported tanks are very vulnerable to tank-killing teams. They clearly remain vulnerable to the anti-tank weapons available now.

- While modern Russian armoured vehicles have been destroyed, many of the Russian vehicles destroyed have been old or even obsolete. The T72 tank entered service in 1973, and the presence of museum-ready T62s suggests a shortage of modern platforms in the Russian fleet.15 The BMP-1, an IFV, was too poorly protected for service in Afghanistan against the mujahidin, yet has been used in Ukraine.

- The failure of the Russian Air Force to control the airspace above its ground troops and weaknesses in counter-drone systems have allowed Ukraine to locate Russian positions using uncrewed systems. Once a position is found, Ukraine’s artillery bombards the position. The main killer of Russian armoured vehicles has been artillery employed in conjunction with drones as sensor/fire teams.

- The terrible state of Russian logistics has resulted in many tanks and other armoured vehicles running out of fuel and being abandoned. One estimate places captured vehicles as accounting for approximately half of Russian losses, showing how critical it is to have the ability to deploy, sustain and support even the best armoured vehicles.

- Russian command and control has been abysmal, resulting in troops being committed to battle in a disjointed and uncoordinated manner, which has resulted in heavy casualties. Of course, some of this may simply be a new illustration of an old truth about the ‘fog of war’.

To help Ukraine, the Australian Government has donated equipment, including howitzers, and—despite their inferior protection and combat survival—Bushmaster PMVs and M113 APCs (Figure 6).

Figure 6: An Australian M113 being shipped to Ukraine

Source: Department of Defence, online.

A failure of appreciation and skill

Russia’s losses can be attributed, in summary, to a military being caught out at a transition point in the art of war. Its leaders failed to appreciate the lethality of the Ukrainian military, including its ability to destroy Russian systems and platforms, especially its armoured vehicles. And Russia did not provide its forces with equipment, leadership or training appropriate to the conditions. It’s not too strong to state that the Russians invaded Ukraine with a force that wasn’t fit for purpose. This means that, while noting Russian losses, the lesson of the Russian–Ukrainian War is that the jury is still out on the future utility of armoured vehicles employed in other scenarios by other forces.

Russia isn’t the first nation to be caught out by an unanticipated shift in the character of war. In the 1990s, the Canadian Army embarked on a policy to lighten the force, which seemed appropriate for the peacekeeping missions in which it had participated. However, in Afghanistan, it discovered that its wheeled light armoured vehicles—a variant of the ASLAV—were too light for the threat environment. Consequently, Canada decided to up-armour and acquired Leopard 2 Tanks from its NATO allies, which it deployed to Kandahar.16

Casualty avoidance

If the lethality of the modern battlefield has motivated the Australian Army to up-armour, the government has also contributed to that trend by consistently signalling that force protection is a priority for operations. Since the invasion of Iraq in 2003, the government has sent a clear message that it expects the ADF to minimise the potential for casualties. The ADF has responded by providing its deployed forces with rules of engagement that have severely restricted what the deployed force can and can’t do in order to manage risk and by providing protected-mobility transport. By and large, this has worked. Throughout the Iraq War, the ADF had only two fatalities, both non-combat related, while in Afghanistan the toll was 41 killed. For war-fighting missions, those figures are remarkably low.

If the Australian Government wants to minimise casualties, one way is to provide equipment that offers enhanced protection. The IFVs under consideration do that. Of course, there are other ways to minimise casualties that don’t require the purchase of a heavily armoured vehicle. They include a reliance on restrictive rules of engagement, fighting from a distance with forces that don’t directly engage an enemy, avoiding the need to seize and hold ground, eschewing operations that involve close contact with civilian populations, and refusing to fight. In addition, the government could seek diplomatic solutions to minimise the threats that the nation faces. All are valid courses of action, depending on the strategic circumstances and how much risk the government is willing to accept. Yet, in war the enemy also gets a say, in which case keeping soldiers alive may come down to the tools they are given and how they are trained to use them.

Alliance management

Australia’s alliance with the US is the foundation upon which Australian security rests. Every Defence review makes this clear, as do the nation’s leaders. Shortly after taking office, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese met with President Joe Biden and they jointly announced their intention to make the alliance stronger. Albanese went on to say that the two countries were ‘great mates’.17

When Australia has participated in recent US-led coalition operations, it’s done so with the knowledge that joining those wars was the best way for Australia to stand out among the US’s many allies. John Howard understood this when he committed the ADF to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

Australia must build the Army that it believes it needs to provide for its security, but Australia’s security is tied up with the willingness of the US to provide assistance if needed. Thus, while alliance management is not a core factor in the Phase 3 decision, it does have some implications for the ADF’s ongoing interaction with the US military. Since neither of the IFV finalists is American, it simplifies the selection from an industrial relations point of view. However, the compatibility of the IFV with American command and control procedures, for example, could prove important if an Australian force again needs to fight as part of a US-led coalition.

Scenarios

In order to provide additional context for the LAND 400 Phase 3 decision, it’s helpful to investigate a number of scenarios that illustrate possible operations that the ADF may have to undertake. Scenario exploration offers decision-makers an understanding of how capabilities might be employed. They also allow the exploration of a number of situations for which planners can provide force options to government. In this instance, reflection upon different scenarios may also help in ascertaining the type and number of the IFV that the Army will need. To support that reflection, this section offers a number of possible future events with which the ADF may need to contend.

Urban conflagration

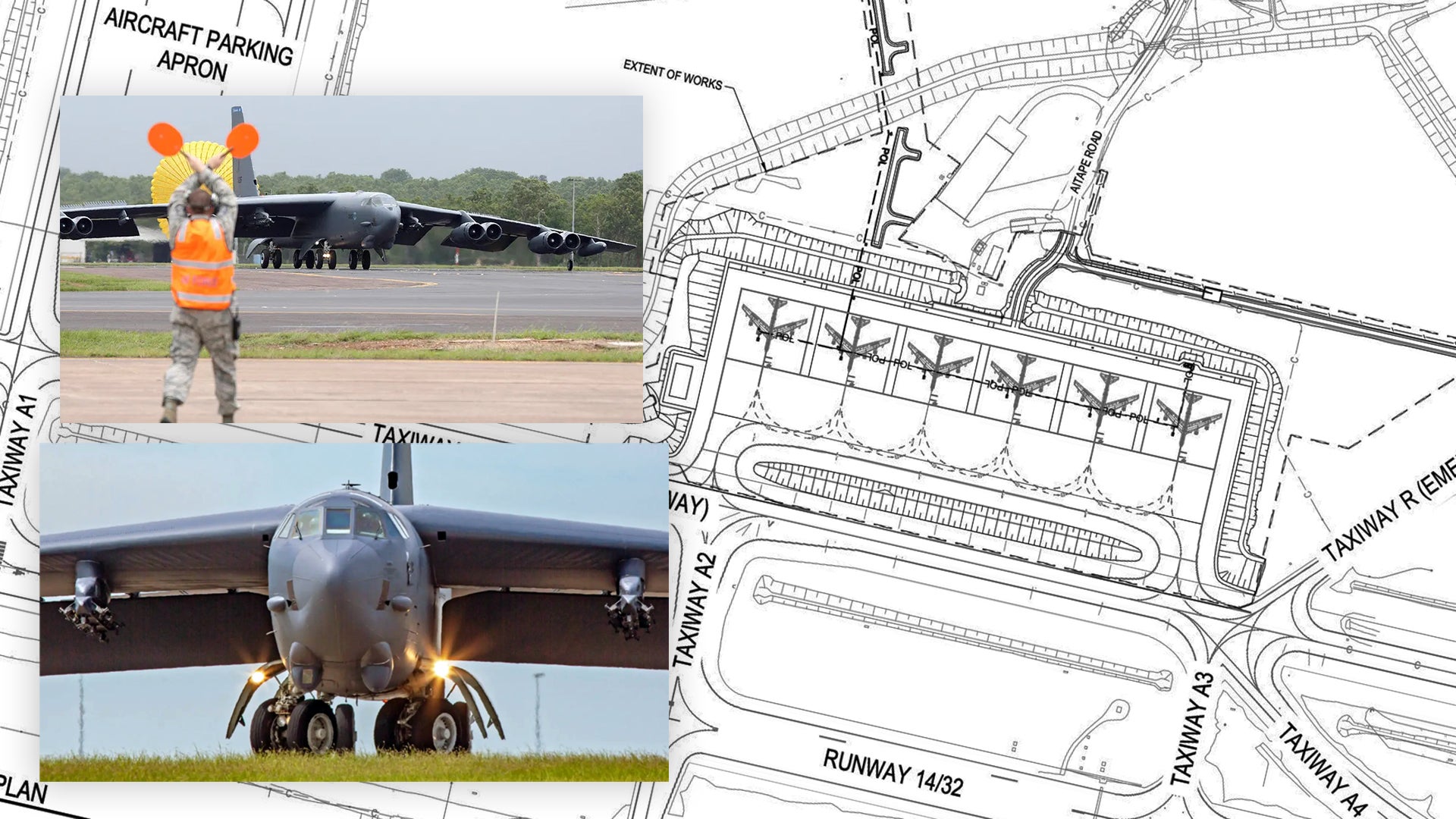

As a result of a coup, the leaders of Papua New Guinea (PNG) flee Port Moresby for Thursday Island in the Torres Strait, where they establish a government in exile. The PNG Defence Force has been disarmed and confined to barracks or has fled into the hills, along with much of the civilian population. Fires burn across much of the city, and an internal refugee crisis looms. Intelligence reports identify a major foreign state’s involvement in orchestrating the coup, and RAAF surveillance aircraft have spotted camouflage-clad mercenaries on the streets. Several foreign transport planes have flown into Port Moresby International Airport, and the Australian Embassy has reported seeing and hearing numerous tracked and wheeled military-style vehicles taking up position across the city. Powerful anti-armour weapons are also in evidence. From Thursday Island, the PNG Government has requested that Australia intervene militarily, restore order and re-establish the authority of the legally elected government.

For Australia, the political collapse of its closest neighbour, its domination by a hostile state, or both, can’t be allowed to stand. In this instance, the RAN and RAAF will establish an air and sea blockade of the approaches, but the liberation of Port Moresby and restoration of the PNG Government will require a land force. The Chief of the Defence Force orders the Army to a high state of readiness, while the ADF’s logistics staff urgently seek commercial shipping.

As the Battle of Malawi demonstrated in 2019, urban fights are brutal, violent and lethal. Soldiers may need to clear every block, every building and perhaps even every room. Fighting can be savage, particularly when the enemy is unlikely to surrender, which is the case with traitors or foreign fighters. To restore the PNG leadership, the Australian Army will need an armoured force to fight into the city and clear it of hostile elements while also establishing camps to aid the displaced population. A high-mobility and well-protected force will be necessary if Australia is to secure its regional national interests.

Controlling the ocean

With the arrival of long-range precision-strike anti-ship missiles, it’s no longer necessary to control the seas from the sea. Instead, batteries of anti-ship missiles positioned on the land can interdict, hinder or prevent the enemy’s maritime movements. An adversary fleet will almost certainly approach Australia from the north and will have to navigate straits that will channel the enemy into a land-based maritime killing zone. Well-positioned Australian anti-ship missile batteries will compound the risk and costs that a hostile fleet will face, and may even deter it from making the attempt. The Army’s acquisition of the M142 High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS) gives the Army this ability.

However, HIMARS will need to be defended from the enemy’s countermeasures. This means that the Army will also need to deploy a combined arms team to secure the surrounding area from both land and air attack. Such a force will require ground-based air defence systems, an armour team of tanks and IFVs and a communications network to link into the joint force, a task that could be performed by the IFV’s communications systems, as well as logistics and other elements. The Army will have the ability to deploy a number of missile nodes, each requiring a covering force for its protection.

Back to the peninsula

Climate change has decimated the agricultural output of North Korea, and the international aid community is unable to provide relief due the global shortage of grain. Hunger stalks the North Korean landscape. In an attempt to preserve his regime and shift the blame for starvation elsewhere, the North’s Supreme Leader launches a surprise attack against the South. The US responds to South Korea’s call for assistance, and troops are quickly on their way. Additionally, the US President speaks to the leaders of democratic nations and requests their assistance. The Australian Prime Minister promises ships and aircraft as soon as they can be made ready, with a ground combat force to follow.

In a discretionary contribution, Australia agrees to send an armoured brigade to Korea. However, due to the limited availability of sea transport, the Australian movement to theatre will be done in stages and largely by hired contract shipping. Consolidation will occur in Japan before movement across the Korean Strait and into combat. Further delaying the land force’s departure is the need to buy war stocks of ammunition due to the limited holdings Australia keeps in country. The North Korean Army is largely an armoured force and, although many of its vehicles are verging on obsolescence, there are lots of them. The desperation of the North’s regime means it will be a hard fight between armoured vehicles and infantry supported by armed drones, artillery and counter air systems. To demonstrate Australia’s resolve and place within the international system, Australian forces are in the thick of the fight.

Continued

www.navyrecognition.com

:quality(70)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/archetype/EKGG54WCGZAUJFE7VSZN3E7XS4.jpg)